The Outrun” is the title of a distant coastal strip of farmland in Orkney. The soil there is worthless as farmland but can never be over-grazed; the Atlantic winds blow it flat, suggesting a metaphor that runs throughout the film. This landscape can represent many things: a healing retreat for weary city folks, a facade of restoration hiding violent truths, or representation of the main character herself, a low-functioning addict fighting inner demons she cannot escape.

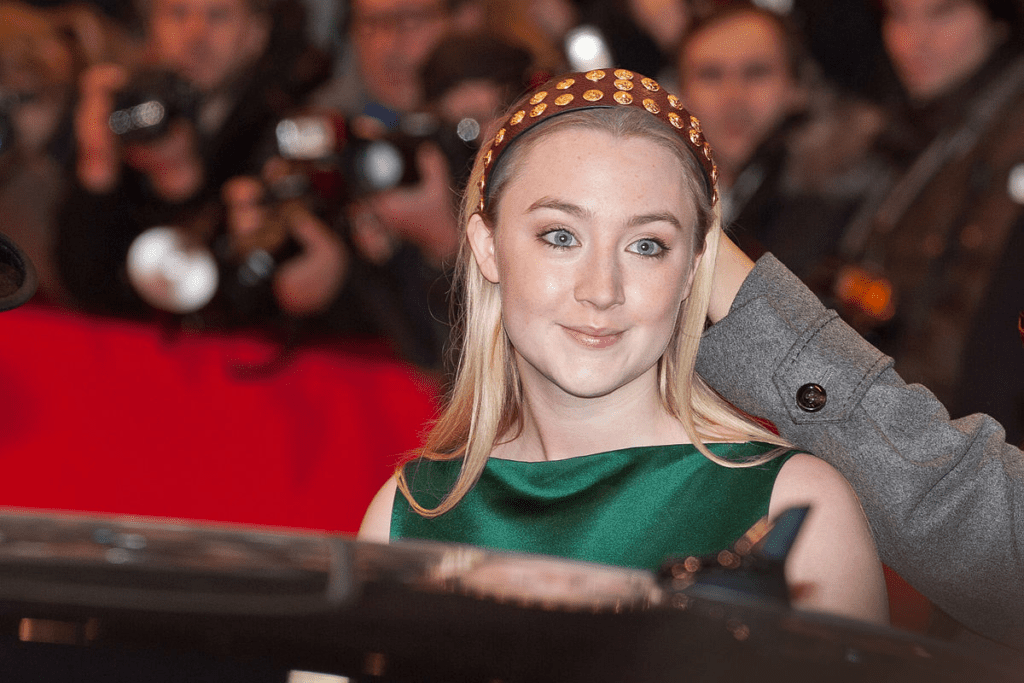

Saoirse Ronan gives a breathtaking performance in this poignant exploration of addiction and recovery, as Nora Fingscheidt directs the adaptation of Amy Liptrot’s memoir of the same name, co-produced with her husband, Jack Lowden. There, Rona is a young woman from Orkney who has drifted into alcoholism and depression by pursuing her postgraduate studies in London. The excitement of this newfound freedom is soon dispelled as the sweet-hearted Daynin (Paapa Essiedu) bears down on Rona in an increasingly toxic relationship until things quite inevitably take a turn for the worse and the detritus of her addiction is laid bare.

Rona leaves rehab at the end of her chaotic twenties to return to Orkney. This becomes part of the bid to recover some sort of control over her own life, as she volunteers for the RSPB to rescue habitats for the corncrake. Perhaps the only interesting scenes in this film are those of her working for the RSPB: here is where one would find the film to be at its most ‘alive’, a lot more profoundly resonant than the dreamy voice-overs about Orkney mythology and its magical creatures, who occasionally appear accompanied by whimsical animation.

Orkney is never romanticised but as a place of stark beauty and isolation. The feeling of loneliness in the battered cottage by winds has been put across very effectively as if echoing sentiments from poet Ted Hughes when he says “This house has been far out at sea all night.” The islands seem to be breathtaking in nature but at the same time intimidating as well, seeming to challenge one in silence amid its tranquility. With Rona’s return, she comes along with complications of her family life. Her parents, Andrew and Annie—played powerfully by Stephen Dillane and Saskia Reeves—are now at pains about their painful separation. Andrew’s problem is suffering from bipolar disorder, which his drinking thrusts upon him. This puts his life in disorganization in a caravan. On the other hand, Annie has attempted to find solace in Christianity. Rona was caught between these two worlds wrangling with the fact that her passions and her tendency to addiction resonate with her father’s. This introspection raises haunting questions of whether survival requires her detachment from him, much like her mother has done. Is this real reason for Rona coming back home?

Ronan infused every frame with raw and focused presence. This captures drunkenness and the fragile state of sobriety with stunning immediacy. There is a poignant moment in a 12-step group in which Rona confesses to her craving for the rush of intoxication. Later, going shopping in Orkney, the camera catches sight of a row of bottles of booze behind the shopkeeper as Rona, composed and blank, rejects every temptation; she wants nothing else. It is a nutshell, to be frank, to summarize this scene and tell you of the emotional intensity of the movie as well as Ronan’s incredible talent in capturing a gamut of emotions.

“The Outrun” provokes the viewer to reflect on the nature of addiction and recovery and the complex bonds that tie us to our past. As Rona confronts her demons in the wild beauty of Orkney, she is transformed into a symbol of this battle to redemption and self-discovery. The film testifies to resilience, showing how one may ride the turbulent waters of life and addiction and seek a path toward healing.

Out to come into UK cinemas on September 27, “The Outrun” is an affecting journey through pain, hope, and the most painful process of reclaiming one’s identity against the stunning yet harsh landscapes.