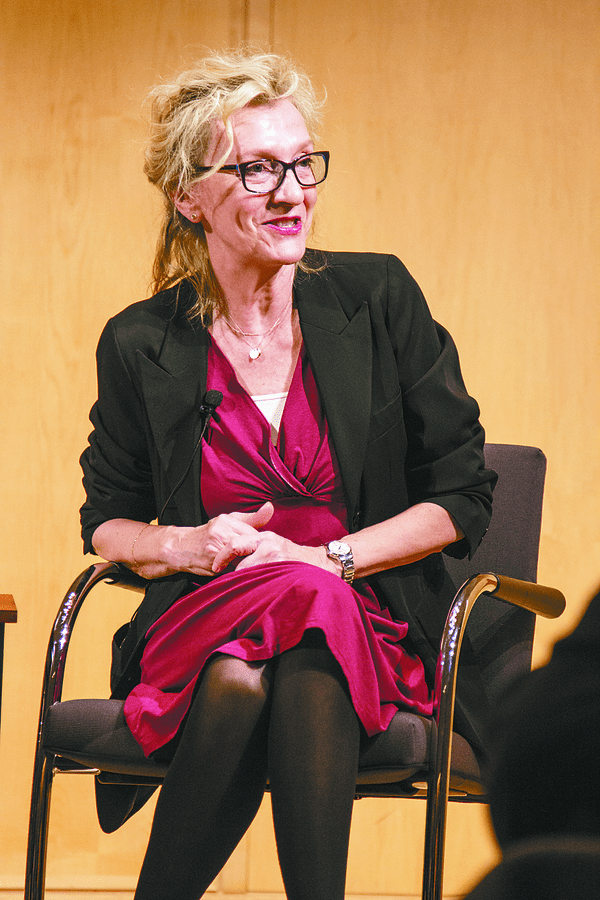

Into her 68th year, and with a Pulitzer Prize to boot, Elizabeth Strout continues to beguile readers and critics alike with her incisive and absorbing novels. Born in Maine, which she still spends a great deal of time in, Strout’s novels often capture something of the spirit of her upbringing. Her latest novel, Tell Me Everything, brings together three characters readers have loved: the reflective Lucy Barton, the irascible Olive Kitteridge, and Bob Burgess, a character who had his first outing in The Burgess Boys. As winter gives way to spring in New England, Strout’s novel unfolds with rare eloquence on themes of loneliness, human connection, and the restorative power of stories.

Strout’s idea to bring the three together came from an unlikely place. Though she never planned to revisit the same characters, she found herself drawn to the idea of bringing Olive and Lucy together. “I just thought it would be so much fun,” she admits, acknowledging that Olive’s initial disdain for Lucy added an intriguing dynamic to the story. The working title, The Book of Bob, speaks to Strout’s preoccupation with Bob Burgess-a man she describes as “fundamentally decent,” yet “oblivious to his own virtues.” She wanted for Bob to come out of his semi-retirement and take on something big.

Weaving a number of characters and their different storylines together was somewhat a risk for Strout. She did wonder whether or not her readers would be tolerant of such a huge cast. However, she does keep her readership company during the time she is writing. Across from Strout is a mental picture of a patient but discriminating reader, and she writes to that person-to craft stories interesting and worth reading.

In Tell Me Everything, Lucy and Olive debate storytelling, and Olive says, “If there’s going to be a story there has to be a point.” But Strout views it otherwise. “It’s the telling of the story as one person perceives it that’s the point,” she says, which seems to dismiss convention in the structures stories take.

Another aspect of the novel which Strout kept open was the developing relationship between Lucy and Bob. She didn’t outline or plan how their relationship would turn out, even as she felt her way through the story with them. This organic telling of the story reflects her general philosophy of writing: spontaneity rather than planning.

The secret depths in people’s lives, however, remained the pivot point for Strout’s interest. She would consider how every person has a different story, just like that tends to be some kind of reassuring theme in her work. “It’s so interesting to think about the vast variety of things that can take place within one person’s life,” she says. This interest in the stories not spoken of by others gave her ammunition for her creative work long ago.

Growing up, Strout was drawn to writing from a young age-in large part because of her mother, an English teacher who had a natural talent for storytelling. It would be in her 40s before Strout’s first novel, Amy and Isabelle, would be published, but she, too, had spent many years writing and rewriting. She claims that the critical improvement of her work, bit by bit, and a realization that she needed to welcome her own voice rather than trying to adjust herself to some prevalent literatures at that time are responsible for her persistence.

It’s easy to see why people connect Lucy Barton with the author, but though Strout says the isolation in her experience does share similarities with her novel, she then immediately demarcates her story from that of Lucy Barton: “My own story was a parallel experience-that feeling of being apart-but really quite different from Lucy’s.”.

Currently, Strout is at work on another, this time with a protagonist who is not a Mainer—a school teacher whose very ordinariness masks a profundity that is just bottomless. And she’s very enthused about this character and about how the story reveals the extraordinary in something which seems so ordinary.

Looking ahead, Strout isn’t so sure about revisiting Lucy, Bob, and Olive, but on the subject of Olive Kitteridge, she remains resolute: a character she knows will figure prominently in her work from now into the future.

Excerpts from Jeffrey Toobin’s American Heiress satiate her reading appetite; she reverts to The Journals of John Cheever and reflects on how she has changed over the years. She also dearly loves The Collected Stories of William Trevor, a book that is re-read for its soft, haunting stories.