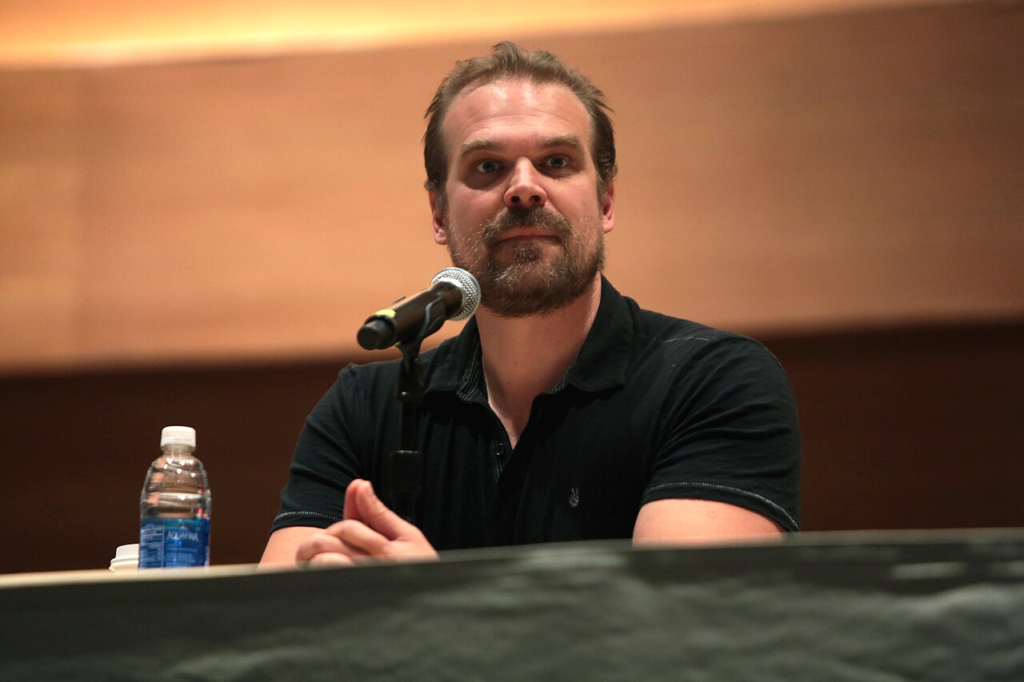

David Harbour has reached a stage in his career where fame no longer feels like a shield he needs to hide behind. Known worldwide for his role as Jim Hopper in Stranger Things, Harbour has recently spoken with striking openness about living with bipolar disorder and the role that long-term, intense psychotherapy has played in helping him build a steadier life. His reflections are not dramatic confessions meant to shock, but measured accounts of survival, self-awareness, and daily responsibility. In an industry that often rewards perfection and silence, his honesty stands out for its calm clarity.

Living with bipolar disorder is often misunderstood as a cycle of extremes that comes and goes without warning. Harbour’s experience shows something far more complex and persistent. He has shared that his condition was formally identified in his mid-twenties, after a severe manic episode led to hospitalization. Before that diagnosis, he recalls periods of intense energy and inflated beliefs that felt, at the time, meaningful or even spiritual. Like many people with bipolar disorder, those early symptoms were confusing rather than obviously medical. It took crisis and professional evaluation for the pattern to finally be named.

What makes Harbour’s story resonate is not the moment of diagnosis, but what came after. He did not step away from acting or retreat from the pressures of Hollywood. Instead, he continued to work while quietly grappling with addiction, unstable moods, and the internal consequences of untreated mental illness. This period of his life was not marked by sudden transformation or instant healing. It was messy, prolonged, and often discouraging. That realism is part of what gives his words credibility.

Harbour has spoken about entering therapy in the late 1990s, initially as part of his recovery from substance addiction. At that stage, psychotherapy was less about managing bipolar disorder directly and more about confronting unresolved emotional pain. Like many people who seek treatment after addiction, he was forced to look backward before he could move forward. Therapy helped him identify patterns of avoidance, self-destruction, and emotional numbness that had shaped his behavior for years. It was not comfortable work, and it was not quick.

Over time, psychotherapy evolved from crisis management into something deeper and more structured. Harbour has described his current therapeutic work as intense, a word that reflects both emotional effort and long-term commitment. Rather than focusing only on symptoms, this approach examines how mood, identity, relationships, and self-worth interact. For someone living with bipolar disorder, this kind of therapy can help recognize early warning signs, question distorted thinking during mood shifts, and create routines that reduce instability.

One of the most striking aspects of Harbour’s reflections is how ordinary he makes the process sound. There is no suggestion that therapy magically solved everything or erased his condition. Instead, he frames it as maintenance, similar to physical training or learning a craft. Progress is measured in awareness rather than perfection. Stability comes not from eliminating difficult emotions, but from understanding them well enough to respond instead of react.

This perspective challenges the popular narrative that mental health recovery follows a neat arc. Harbour’s experience suggests that improvement often looks like consistency rather than change. Showing up for therapy, staying sober, taking medication when prescribed, and accepting limits become quiet victories. These actions rarely make headlines, but they are the foundation of long-term functioning.

His openness also carries weight because of his professional success. In entertainment, mental illness is often romanticized or hidden. By speaking plainly about bipolar disorder while continuing to work at the highest level, Harbour disrupts the idea that vulnerability and competence cannot coexist. He does not portray himself as cured or broken. Instead, he presents himself as responsible for managing a condition that is part of his life, not the sum of it.

There is also a broader cultural significance to his willingness to talk. Public figures who acknowledge serious mental health conditions help reduce stigma, especially when they avoid sensational language. Harbour does not frame bipolar disorder as a superpower or a curse. He treats it as a medical and psychological reality that requires care, discipline, and honesty. For people living with similar diagnoses, that balanced framing can be quietly reassuring.

At the same time, Harbour’s story does not suggest that therapy alone is enough for everyone. Bipolar disorder is complex, and effective treatment often includes medication, lifestyle adjustments, and strong support systems. What psychotherapy offers, in his case, is a way to make sense of those tools and integrate them into daily life. It becomes a space to reflect, recalibrate, and stay accountable.

Listening to Harbour speak about his mental health, there is a noticeable absence of self-pity. He acknowledges suffering without centering it as his identity. That tone likely comes from years of therapeutic work that emphasizes responsibility over blame. It is a reminder that mental illness explains behavior, but it does not excuse abandoning care or self-awareness.

Public reaction to such disclosures is often mixed. Some praise the courage it takes to speak openly, while others question whether celebrities’ experiences are relatable to ordinary lives. Both reactions hold some truth. Harbour has access to resources many people do not. At the same time, the emotional work he describes, confronting painful patterns, staying consistent, and accepting limits, is deeply familiar to anyone who has engaged seriously with mental health treatment.

What remains unanswered, and perhaps always will, is how society can better support people before crisis forces intervention. Harbour’s diagnosis came after hospitalization, a turning point that many experience too late. His story invites reflection on earlier recognition, reduced stigma, and the normalization of seeking help before collapse.