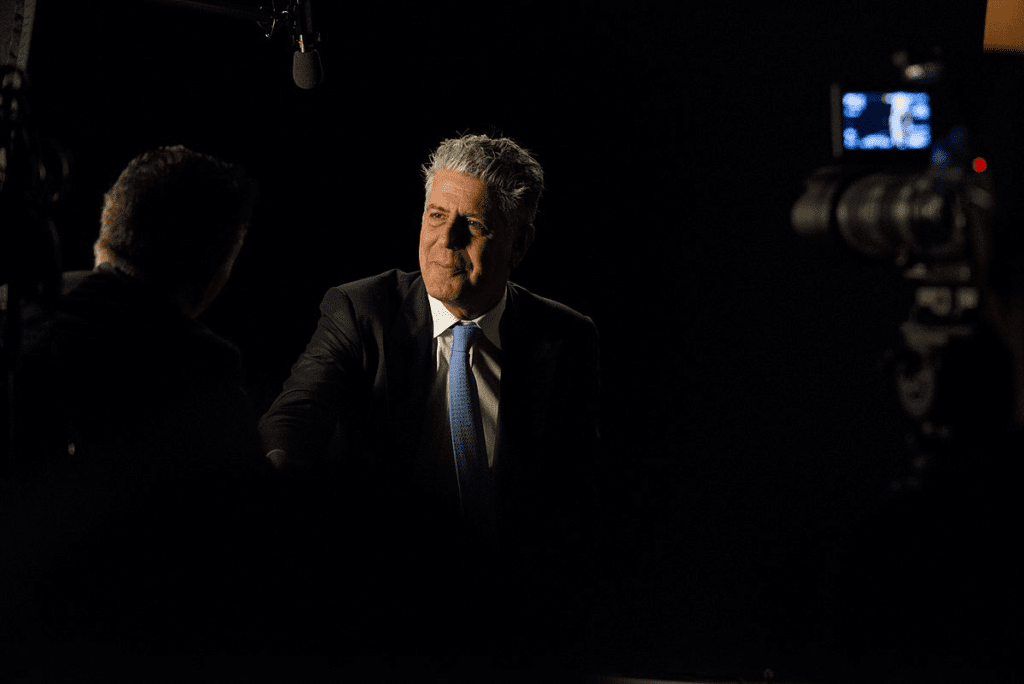

Anthony Bourdain, one of the most famous food critics and television hosts, had a lifelong affair with music. Unlike many celebrity chefs who smelled of arrogance without a shred of a bad boy attitude, Bourdain did live up to his non-conformity. It was reflected in his approach to food-as much as in his musical tastes. In fact, much of his worldview was made by a great affinity he had for punk music while growing up in New York City, at the time it got most notorious back in the 1970s.

Growing up in that kind of rich musical landscape, Bourdain gravitated toward early punk bands: the New York Dolls, Dead Boys, The Stooges, and Bad Brains. He might have lacked the whole mohawk-sporting, safety-pin-wearing, clothes-tearing-stereotypical punked-out look, but the essence of punk permeated his person and weltanschauung. For Bourdain, the punk attitude was not so much about the music but an attitude toward living whereby one eschewed the mainstream, did not take no for an answer, and surged along with life authentic. He never settled with the food of the place; instead, he’d often thread his experiences with the local music culture into the fabric of his shows. This was perhaps most clear in the very first episode of Parts Unknown, in which Bourdain visited Myanmar in 2013. There, he spent time with a local punk band called Side Effect, which still performs to this day. The band was, like Bourdain, a raw, futuristic version of rebellion that he deeply resonated with.

It was not just food Bourdain did during his sojourn in Myanmar; he tries to understand the society of Myanmar. Definitely, the episode shall feature discussion about local cuisine; he had far more curiosity than food could satiate. He wanted to understand the spirit of the place, and music became a key part of that discovery. Coming from the punk scene, it was no surprise he connected with Side Effect, talking about how much they loved music and divulged on how fed up they were with some of the bands.

During one memorable moment, while dining with the band, Bourdain turns to them and asks, “What American bands do you hate?” It’s a question he might have more easily answered himself, considering his strong opinions on the subject. After deliberating for a beat, Side Effect says, “Creed,” a band long maligned for commercializing rock. Bourdain’s reaction? “Yes! They are, like, the worst band in the history of the world.”

Though Bourdain’s comment was certainly laced with hyperbole, it nonetheless resonated deeply with him and the band. Creed was, after all, a post-grunge band that reached staggering commercial success throughout the 1990s, which represented everything Bourdain-and punk purists-repudiated. Creed’s polished, corporate rock sound was in just about every way the polar opposite of punk, which was raw and rebelled against the mainstream, embracing any kind of imperfection.

For Bourdain, music was not just a backdrop to life, but a part of his very identity. Bourdain despised Creed because it was a phonily artificial act. Its success was premised on a slick and soulless formula targeted at mainstream audiences. Punk shaped Bourdain’s ethos: a scorched-earth rejection of that mainstream in favor of something more real and gritty. For Bourdain, the music of Creed was the very definition of a cash grab, devoid of passion and raw emotion, which he loved so much in the punk movement.

The reason Bourdain decided to go at Creed is pretty interesting. The band got together once more in 2009, after a post-breakup hiatus, putting out new material and going on strings of world tours. As he filmed the Myanmar episode in 2013, the reunion of Creed had reminded many music fans, but particularly those that were rooted in scenes of punk and alternative of that commercialization and commodification that seemed to dilute very much the spirit of rock. To a man like Bourdain, who had lived through and appreciated the rebellious energy of punk, seeing a band like Creed dominate the airwaves was doubtless an affront to everything he valued in music.

Ultimately, Bourdain’s hate for Creed had little to do with their music and everything to do with what they represented: in a world where authenticity and rebellion were sacred, Creed’s success symbolized the triumph of commercialism over art. And for Bourdain-who spent his life in search of the authentic, whether it be food or music-that was an unforgivable sin.