A 93-year-old woman with dementia has died from consuming laundry pods that she most probably mistook for sweets due to their bright and eye-catching packaging. Now, the case has encouraged a coroner to raise concerns over the threat of such products, not only towards children but vulnerable adults with cognitive impairment, and also to push for stricter safety regulation.

In a heartbreaking case, a London lady aged 93, suffering from dementia, Elizabeth Van Der-Drift, lost her life after she mistakenly ate some toxic laundry pods. The tragedy resulted in stern warnings being issued by the Coroner over the potential risks posed by such brightly colored products, especially to vulnerable adults like these afflicted by dementia.

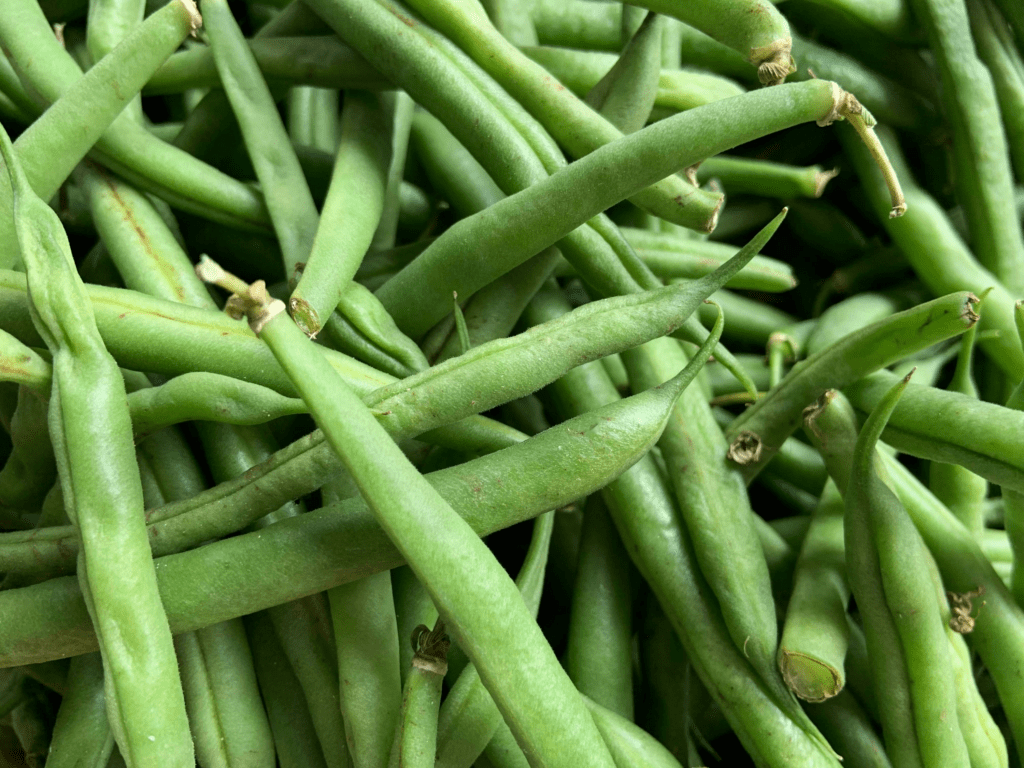

Elizabeth had lived with dementia for several years. It often caused her to become confused and forgetful. In mid-March, she came across a container of laundry pods. Their bright, candy-like colors—pinks, whites, oranges, yellows, and greens—might have made them look like sweets to her. Without realizing the danger, she bit into at least one of the pods. The toxic detergent inside quickly made her sick.

Soon after ingestion, Elizabeth began experiencing acute stomach pains and shortness of breath. Her carer, frightened by her symptoms, immediately called the ambulance, and she was quickly taken to the hospital. Unfortunately, despite all the efforts of the respective medical staff, Elizabeth died a few days later, on March 19, 2024. An inquest held into the death was concluded to be accidental, but preventable.

Ian Potter, chaiman of the inquest, said he was extremely concerned about the design and the packaging of the laundry pods. He said, although there appeared to be awareness about the potential risks these products could pose to children, very little thought had been put into the potential risks to adults who have dementia or any other cognitive impairment.

Potter said the bright, attractive colors of laundry pods have simply been part of a more general trend throughout an entire industry, fostered by consumer demand, aiming to grab the customer’s attention. Such designs are meant to convey attractiveness and stopping power, but they can also be deceptively dangerous. A person with dementia, for instance, might view a pod as being perfectly safe—almost like candy—whereupon a terrible accident will happen.

The coroner also noted that the container in which these pods are placed was also poorly designed. It had no effective safety features at all that would deter an individual who had literally any level of manual dexterity. This thus allowed Elizabeth to gain entry to the contents of the pods and ingest them, ultimately resulting in her death.

For Potter, his report was a Prevention of Future Deaths report not aimed only at the manufacturer of the laundry pods involved in this incident but at the wider industry and government regulators. He has also sent his warnings to the chief executive of the Office for Product Safety and Standards, as well as the secretary of state for health and social care and the director general of the UK Cleaning Product Industry Association.

Potter greased a very important pole in the wheels of his argument: there are laws, such as the Food Imitations (Safety) Regulations of 1989, that disallow the distribution of any product that might be deceptive and give out the appearance of food but seem to fall short of protecting adults with dementia. The concerns here are mainly with children, who might mistakenly eat dangerous products that resemble food. But, Potter argues, the rules don’t go far enough to protect those with cognitive impairments, and aren’t being effectively enforced.

Elizabeth’s story is one that should remind you of the vulnerabilities lived by people who are diagnosed with dementia. Her death is a dramatic call to wake up about the protracted risks that specific household products present towards individuals faced with cognitive challenges.

The PFD report is being published up to October 8, 2024, to the addressees who are required to communicate the measures that they will take or have taken with respect to the tragedy. If they do not take any measures to this effect, then they will have to explain why. It is going to be taken with a lot of weight in deciding whether or not to change product safety laws for the protection of these classes of society.

The tragic death of Elizabeth Van Der-Drift is a glaring example of how something as simple as bright packaging can have such destructive consequences. It is a clarion call to manufacturers, regulators, caregivers, and others to rethink their activities in view of the very special needs of this growing group of patients with dementia or other cognitive disabilities. With changed product design and some adjustment in safety standards, similar tragedies in the future can hopefully be averted.

While nothing will bring back Elizabeth, her story might mean that other people don’t pay a price for their lives with it. Maybe this will have the industry re-evaluate how it defines safety, putting more safeguards in place in an attempt to ensure products are safe for everybody, including those who are most vulnerable among us.